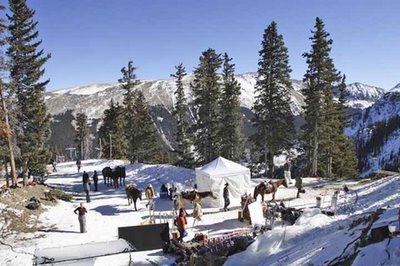

Photograph of Daniel Lanois in Taos by Rick Romancito, The Taos News

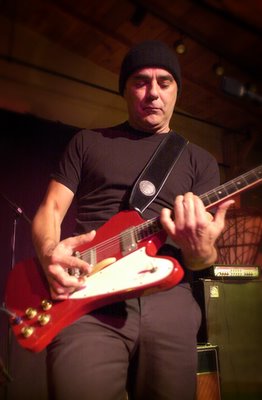

This was an interview I conducted in 2003 with musician Daniel Lanois, whose legendary collaboration with U2 produced "The Joshua Tree" album. Lanois was getting ready for a performance in Taos, New Mexico.

Q: We’re looking forward to your appearance here in Taos.

Daniel Lanois: Oh, yeah, me too. You know, it’s been awhile since I’ve been in New Mexico. Great to see what’s going on your town.

Q: We’re a fairly small town but there are a lot of creative energies going around here. I understand you grew up in a small town in Canada.

A: That’s right. I’m French-Canadian. As a French kid and, uh, my mom transported the family when I was about 10 to the Toronto area, so it’s all, uh. The town itself is called Hamilton, which is a steel town like Pittsburg. It’s like a sister city to Pittsburg. And it’s a tough place. It’s industrial, it’s all about steel. You want to do music, you’ve got to struggle. As I talk to my friends, they say ‘Well, you should consider that somewhat of a blessing.’ You know, having come from the unlikely side of the tracks because it’ll make a fighter out of you.

Q: What were your early influences or interests in music? How did you get into all of that?

A: It was violin-playing around the house. My dad and my grandfather were both violin players. It was kind of a poor setting. Nobody had any cash, so it was a self-entertainment society. The weekend was largely about bustin’ out the violins and doin’ some singin’. And, I think, there was something sweet about that, that kind of entered my bloodstream. It was certainly melodic music, definitely French. Those roots are still with me. Those melodies still make their ways into my songs, like, there’s a song on my record (“Shine”) called “As Tears Roll By.” It pretty much has one of those old violin melodies in it.

Q: As you were becoming more interested in music, was there any one thing that did it for you, that changed your direction in life and made you decide this is what you were really going to do?

A: I guess I looked at the options that were available to me as a teenager and I realized that my gift and my interest were really sort of my ticket out of the potential blaséness I saw on the horizon. It was just a magic world for me, you know, a place where imagination can run wild.

Q: Was there any one particular break for you?

A: You know, I think nighttime radio really changed the course of my life. As I told you, I lived in this town called Hamilton, but geographically between Buffalo, NY and Detroit, Mich., and there was a lot of really great radio at that time, in the 60s, that kind of energy, and, for that matter, quality. There was a lot of rhythm and blues music, Motown, all that stuff. Psychedelic music was starting to bust. I think that nighttime radio, the mystery of it is what drew me into it. Coming into sexuality. It was just a really vibrant time and I just decided that I wanted to be on the magic side of the fence.

Q: Well, you certainly seem to have gotten onto the magical side, having worked with U2, Brian Eno and Emmylou Harris.

A: Yeah, those are, speaking of imagination, those folks have really got it. And it’s contagious. When you’re hanging around, working, brainstorming with people who are real smart and have vision, it rubs off and it’s just sort of a great arena to be in. you know, I met Brian Eno, my skills were pretty high when I met Brian, but I had not had a chance to hook into something quite the way I was imagining and he presented me with some possibilities. Probably the greatest lessons were dedicating yourself to something that you believe in. No so much the potential commerciality of it but just the musicality. Those are the lessons that ultimately stay with you. They’re more esthetic than financial.

Q: How would you define your particular “sound” to your music? It’s been referred to, in some ways, as kind of “tripped out,” “psychedelic” and “melodic.”

A: Yeah, well you’re comin’ in with some big compliments there. “Tripped out,” “psychedelic” and “melodic,” I’ll accept all that. Melody is at the top of the list of priorities. Tripped out, let’s just say that means breaking some kind of ground sonically — and it’s the ongoing mystery of records to me. You know, the potential of like reinventing an instrument or just looking at it in ways its never been seen before. That’s it. It’s what keeps me inside the laboratory.

Q: A lot of “Shine” was recorded in Mexico.

A: I went to Mexico, somewhat on a sabbatical and mostly to get away from the usual urban crossroads. You know, when you look at your life and you think, Jeeze, I’ve spent most of it in cities. I wanted to be exposed to another kind of culture. Not only did I think that the Mexican music sounded the best on juke boxes, I wanted to be in a place where people were concentrating on their own thoughts and it wasn’t so much about cramming in as much of a day into a cell phone as possible. But, without any doubt, the way of looking at the world, the imagination that exists south of the border is appealing to me.

Q: So you stepped back from the hectic music business. That must have been quite a change?

A: It’s nice to step out of the race, whatever the race happens to mean to you, because we get pretty used to our environment and we’re quite resilient as human beings, and we accommodate whatever gets thrown at us. The fact is, a change goes a long way and it’s nice to visit other cultures. I would highly recommend it to any North American.

Q: You might get a little hint of that when you come to Taos. This is a very small town and it has some very rural sensibilities but also some fairly cosmopolitan attitudes here as well.

A: Well, it’s great. It’s a magic part of the world, for sure. Are we close enough to (get) some stragglers from Albuquerque and some of the other neighbor towns?

Q: Possibly. Albuquerque’s about two and a half, three hours away.

A: Right, that’s kind of a long way.

Q: Santa Fe’s about an hour and a half or so.

A: Right, ok. Well, when I asked my agent, I said “What’s up? Why aren’t we playing Santa Fe?” And he said, “Well, Taos was your best offer.” (laughs)

Q: Well, it’s a pretty good offer. Taos is a whirlwind.

A: I’m looking forward to it.

Q: What’s the best part of producing? Do you ever find it frustrating, being a musician?

A: When I’m producing, I know that come the end of the record I won’t have to be touring or publicizing or promoting it. So, it’s a very selfish situation. I get to be creative and then I get to go to bed. But I don’t believe there are any frustrations. I see there’s a lovely opportunity to have an exchange with people. I really believe in the power of osmosis. If you’re excited about your work and you bring something to the table, and an artist does the same. It’s just a really lovely communication and a chance to exchange some philosophies, and then those’ll bleed into the next project that comes along, whether it be my own or someone else’s. That’s just the power of evolution.

Q: I know a lot of local fans would be interested in hearing a little bit about your relationship with U2 and Bono.

A: It’s an entirely creative relationship that I have with those guys. And a musical one. But probably the part of it that gets the smallest amount of attention is the kind of spiritual bond between us. It’s the most intangible. Obviously, it can’t be measured by technology. We call it the Heart and Soul content. It’s just something that happens between us, chemically. Not induced by drugs, mind you. Just talking about old fashioned human exchange. They’re humanitarians and so am I.

Q: There’s a lot of passion in their music, as well as social and political awareness too. Is that part of your relationship as well?

A: I try and include political awareness in my own work. You know, that song “As Tears Roll By” has some references to the Tower of Babel, and it’s sort of my backdoor way of dealing with an empire’s perspective. Things get bigger and bigger and bigger and we stop looking at the soil we’ve built our buildings on. Eventually, the spirit may come crying out of the ground. How’s that for a bit of New Mexico perspective?

Q: You got it right there.

A: It’s the balance that’s real important, at any given time. As a race, we will be fascinated with our current flavors, perhaps they will be technological ones or commerce related ones. But, you know, we step back from whatever the current buzz might be, I think we’ll certainly see a broader picture. I address some of those issues in that song.

Q: You’ve done a number of pieces for films (such as Billy Bob Thornton’s “Sling Blade”). What’s the big switch that you have to click over when you do music for movies as opposed to music for your latest album?

A: I’ve always felt that they were all connected. Being a visual person, I had a great opportunity to work with Billy Bob Thornton and his movie, “Sling Blade,” and I hope it’s always that way for me, that one-on-one relationship. But it’s very suitable for me because, until my music fully becomes song, oftentimes it will, sort of, half-painted canvasses are really great for film because the absence of certain ingredients allows the imagination to fill in the blanks, because that’s the thing to remember about music for film. In a way, it’s kind of incomplete music and it becomes complete with the presence of the picture. It’s perfect for me, given that I have as big a library as I have of beginnings.

Q: Often filmmakers say it’s difficult to find a really good musician-composer to do film music because they want their music to stand alone. Because, when it’s being used in a film, it has to serve the visual half of the creative equation.

A: That’s a good point. Well, I feel that, you know in the 60s there were some pretty adventurous filmmakers, why don’t we say that “Easy Rider” was the beginning of like rock songs in movies, or “Apocalypse Now.” So, let’s take the immediate climate of our society and stick it in the music, just like “Here’s what’s goin’ on and we’re gonna mirror that by putting in a bunch of this stuff in the movie, it really worked great. I think, as the pendulum swings, it’s gone too far. And when it reaches a point where decisions are based on commerce rather than filmic and musical impact, i.e. a label will say “We gotta get this band doing a song in that movie.” So, oftentimes, you get things that’re just rammed into films and you wonder what the hell’s this have to do with anything? So, I’m hoping, as the pendulum swings, that there’ll be more brave filmmakers who say “I want to work with this individual, because I really believe that their personality, their intensity, their vision, is going to be supporting the spine of this film. Rather than having it be a garnish based on some sort of office decision. I think that we’ve seen some fine examples of that. In the classics, they wouldn’t think of having 20 people making a musical contribution. “Paris, Texas” has a very concentrated soundtrack. It wasn’t about “Let’s get 50 different slide players.” It was “One will be ok.” So, I think, what I have to offer potentially towards film is that very thing. If I was invited to, by a great filmmaker to work on a great film, I would do a great soundtrack. I think it’s probably the way of the future. At least, a slice of it.

Q: Where do you think you’ll be in about 10 years, musically?

A: Ten years? I think that, given I’m going to be putting out records regularly now, about every 10 months I’m going to put out a record, I think I’ll probably be doing exactly the same thing I’m doing now. Putting out records, make them as interesting as possible. I want them to be, you know, still considerations for music listeners in 10, 20 years time. I’m hoping that it’s my slight off-chance at immortality. (laughs)

Q: We all try for that.

A: We’re all headin’ for the same place. We might as well have something we’re proud of there, either hanging on walls or on people’s CD players.

Q: Thanks a lot Daniel, I appreciate your time.

A: My pleasure. Looking forward to coming to New Mexico.